Born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski in a Polish-speaking part of the Russian Empire, Joseph Conrad went to sea in 1874, and drew on his experiences as a merchant seaman for his fiction. In his memoir The Mirror of the Sea, he looks back on the Sydney of the 1870s:

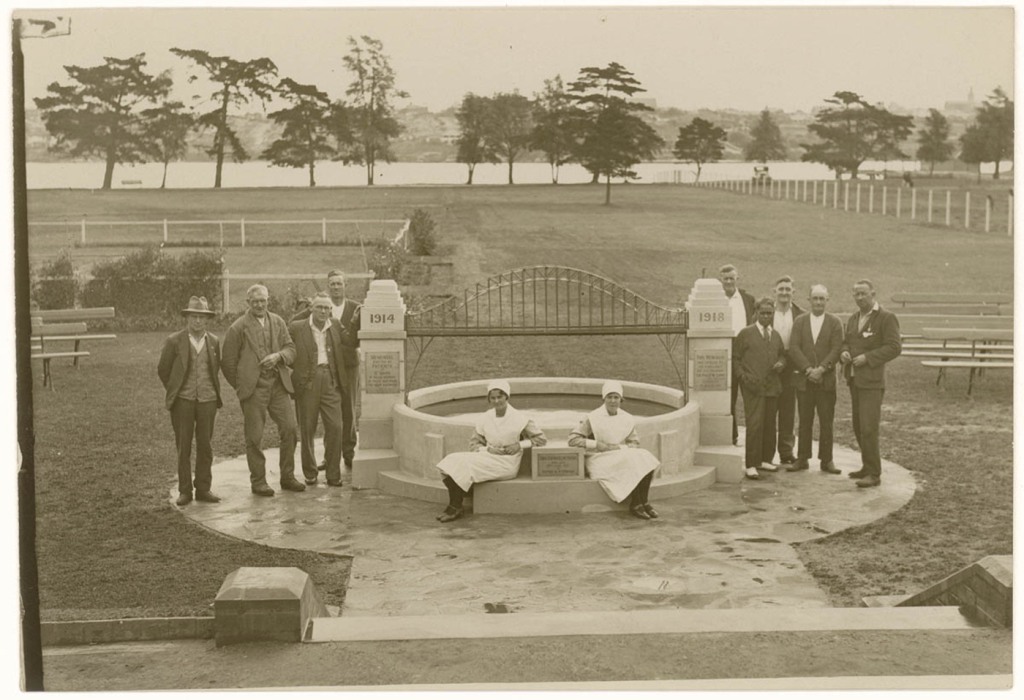

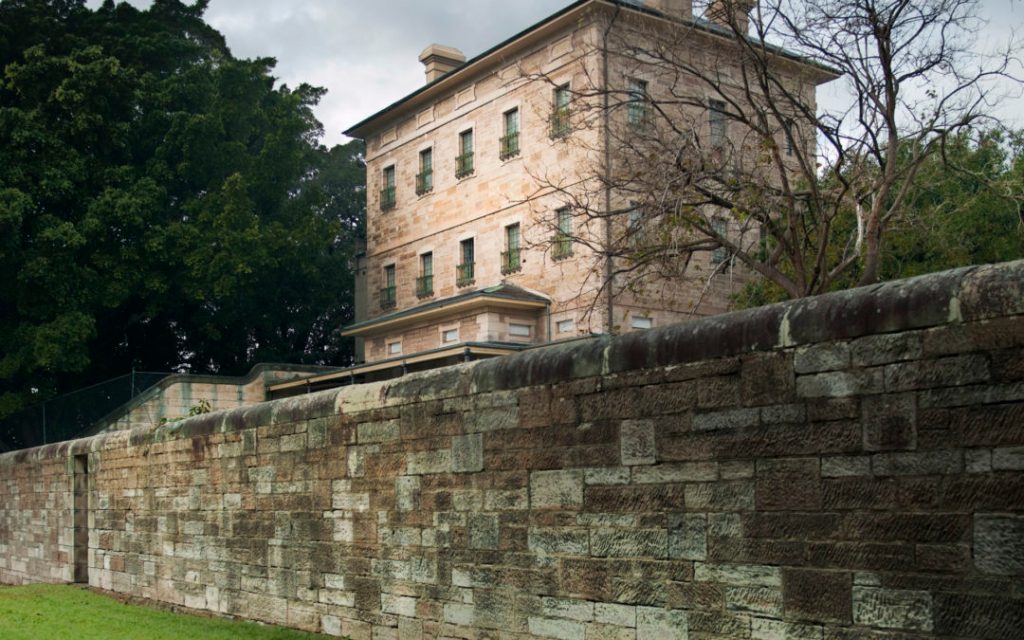

Watermen and their boats at Circular Quay, c.1890. (City of Sydney Archives)

These towns of the Antipodes, not so great then as they are now, took an interest in the shipping, the running links with “home,” whose numbers confirmed the sense of their growing importance. They made it part and parcel of their daily interests. This was especially the case in Sydney, where, from the heart of the fair city, down the vista of important streets, could be seen the wool-clippers lying at the Circular Quay—no walled prison-house of a dock that, but the integral part of one of the finest, most beautiful, vast, and safe bays the sun ever shone upon. Now great steam-liners lie at these berths, always reserved for the sea aristocracy—grand and imposing enough ships, but here to-day and gone next week; whereas the general cargo, emigrant, and passenger clippers of my time, rigged with heavy spars, and built on fine lines, used to remain for months together waiting for their load of wool. Their names attained the dignity of household words. On Sundays and holidays the citizens trooped down, on visiting bent, and the lonely officer on duty solaced himself by playing the cicerone—especially to the citizenesses with engaging manners and a well-developed sense of the fun that may be got out of the inspection of a ship’s cabins and state-rooms. The tinkle of more or less untuned cottage pianos floated out of open stern-ports till the gas-lamps began to twinkle in the streets, and the ship’s night-watchman, coming sleepily on duty after his unsatisfactory day slumbers, hauled down the flags and fastened a lighted lantern at the break of the gangway…

Circular Quay, c. 1888. View from the water looking south to Mort Co. (Woolbrokers) with banners “Many Happy Returns of the Day” (possibly on the occasion of the Centenary in January) and showing people gathered on the quay and a number of launches or ferries and tall ships. (Photo by Henry King 1880-1890, City of Sydney Archives)

A stupid job, and fit only for an old man, my comrades used to tell me, to be the night-watchman of a captive (though honoured) ship. And generally the oldest of the able seamen in a ship’s crew does get it. But sometimes neither the oldest nor any other fairly steady seaman is forthcoming. Ships’ crews had the trick of melting away swiftly in those days. So, probably on account of my youth, innocence, and pensive habits (which made me sometimes dilatory in my work about the rigging), I was suddenly nominated, in our chief mate Mr. B—’s most sardonic tones, to that enviable situation. I do not regret the experience. The night humours of the town descended from the street to the waterside in the still watches of the night: larrikins rushing down in bands to settle some quarrel by a stand-up fight, away from the police, in an indistinct ring half hidden by piles of cargo, with the sounds of blows, a groan now and then, the stamping of feet, and the cry of “Time!” rising suddenly above the sinister and excited murmurs; night-prowlers, pursued or pursuing, with a stifled shriek followed by a profound silence, or slinking stealthily alongside like ghosts, and addressing me from the quay below in mysterious tones with incomprehensible propositions. The cabmen, too, who twice a week, on the night when the A.S.N. Company’s passenger-boat was due to arrive, used to range a battalion of blazing lamps opposite the ship, were very amusing in their way. They got down from their perches and told each other impolite stories in racy language, every word of which reached me distinctly over the bulwarks as I sat smoking on the main-hatch. On one occasion I had an hour or so of a most intellectual conversation with a person whom I could not see distinctly, a gentleman from England, he said, with a cultivated voice, I on deck and he on the quay sitting on the case of a piano (landed out of our hold that very afternoon), and smoking a cigar which smelt very good. We touched, in our discourse, upon science, politics, natural history, and operatic singers. Then, after remarking abruptly, “You seem to be rather intelligent, my man,” he informed me pointedly that his name was Mr. Senior, and walked off—to his hotel, I suppose. Shadows! Shadows! I think I saw a white whisker as he turned under the lamp-post. It is a shock to think that in the natural course of nature he must be dead by now. There was nothing to object to in his intelligence but a little dogmatism maybe. And his name was Senior! Mr. Senior!

Circular Quay , with ruins of Dawes Battery in the foreground with a small steamer berthed in (now) Campbells Cove. The spire and lookout of the AUSN building is at far right. Campbell’s bond stores below the AUSN tower. (City of Sydney Archives)

The position had its drawbacks, however. One wintry, blustering, dark night in July, as I stood sleepily out of the rain under the break of the poop something resembling an ostrich dashed up the gangway. I say ostrich because the creature, though it ran on two legs, appeared to help its progress by working a pair of short wings; it was a man, however, only his coat, ripped up the back and flapping in two halves above his shoulders, gave him that weird and fowl-like appearance. At least, I suppose it was his coat, for it was impossible to make him out distinctly. How he managed to come so straight upon me, at speed and without a stumble over a strange deck, I cannot imagine. He must have been able to see in the dark better than any cat. He overwhelmed me with panting entreaties to let him take shelter till morning in our forecastle. Following my strict orders, I refused his request, mildly at first, in a sterner tone as he insisted with growing impudence.

Circular Quay, c. 1890. (City of Sydney Archives)

“For God’s sake let me, matey! Some of ’em are after me—and I’ve got hold of a ticker here.”

“You clear out of this!” I said.

“Don’t be hard on a chap, old man!” he whined pitifully.

“Now then, get ashore at once. Do you hear?”

Silence. He appeared to cringe, mute, as if words had failed him through grief; then—bang! came a concussion and a great flash of light in which he vanished, leaving me prone on my back with the most abominable black eye that anybody ever got in the faithful discharge of duty. Shadows! Shadows! I hope he escaped the enemies he was fleeing from to live and flourish to this day. But his fist was uncommonly hard and his aim miraculously true in the dark.

-Joseph Conrad, Polish-British, 1857-1924