Set in 1942, Jon Cleary’s novel follows a group of Australian soldiers who have just returned from the Middle East and are on leave in Sydney before being sent to New Guinea. Sergeant Jack Savanna, a radio announcer before the war, has met Silver Bendixter at the Anzac Buffet in Hyde Park: living at Darling Point, the Bendixters are ‘pillars of Sydney society’, well known in the gossip columns. Jack and Silver conduct a whirlwind romance in the week he has in Sydney:

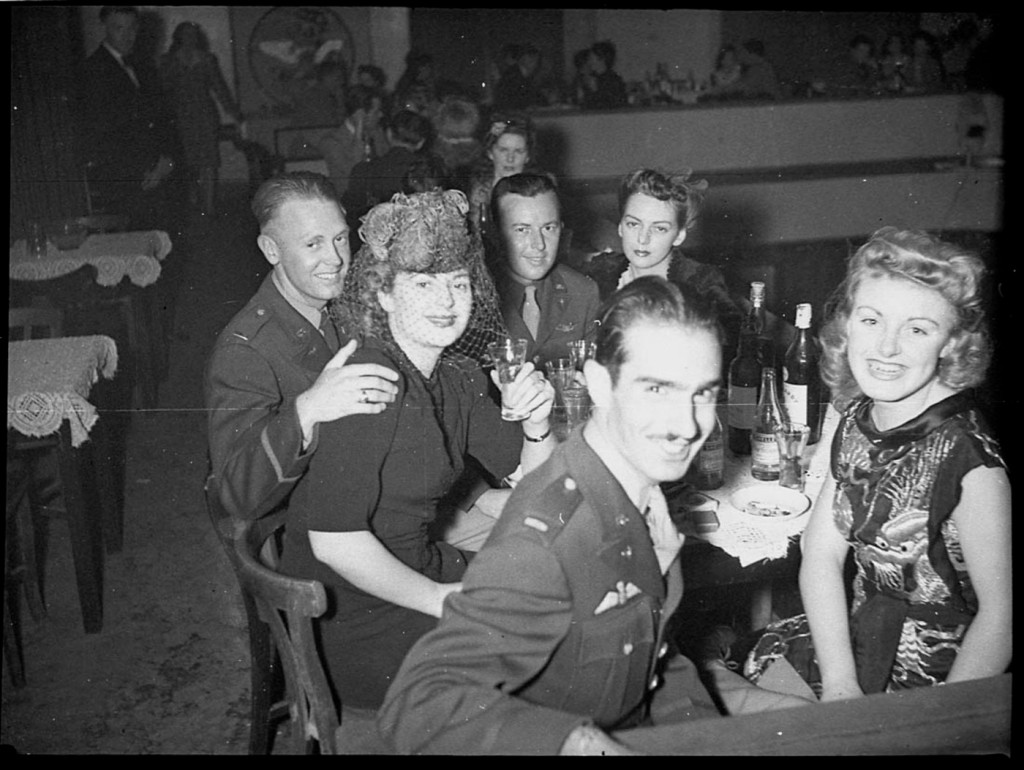

They had lunch next day at Prince’s. They sat close to a table that was fast becoming famous as the command post of certain Australian war correspondents covering the New Guinea front, and behind a table that was already famous as the command post of a genteel lady who covered the Society front. Gay young things were being industriously gay, keeping one eye on each other and one eye on the door in case a photographer appeared. Matrons pecked at their food like elegant fowls, also eyeing each other and waiting the advent of a photographer. Two suburban ladies from Penshurst, having a day out in Society, sat toying with their food and wishing they had gone to Sargent’s, where they could have had a real bog-in for less than half the price. Aside from Jack and the American correspondents, there were only one or two other men in the place, and they looked as uncomfortable as if they had been caught lunching in an underwear salon. Australian men still hadn’t learned to be at ease when outnumbered by women.

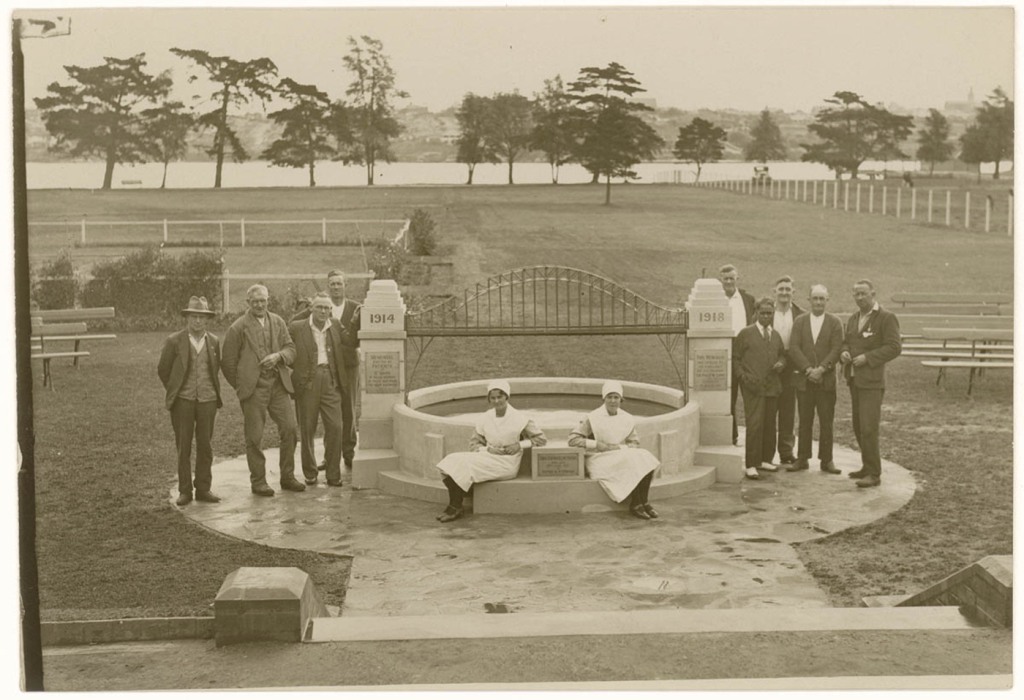

Silver told Jack she had to go to a meeting that night. “It’s some sort of bond rally that my mother has organised for business girls. David Jones’ have lent their restaurant. Everyone has tea and sandwiches, then this war hero gets up and says something. After that, the idea is that the girls all rush up and buy war bonds.”

“I thought they’d rush up and lay themselves at the feet of the war hero. It has better possibilities, I mean as a spectacle.”

“Well, anyway, that cuts out dinner to-night,” she said. “Unless you want to wait until after the meeting.”

“I’ll come along and eat tea and sandwiches. Maybe afterwards, just to set the girls an example, I’ll rush up and throw myself at the war hero.”

That evening, shortly after the stores had closed, he met her outside David Jones’. They went into the big gleaming store and, in a lift crammed with chattering females who looked with an appreciative eye on Jack and a critical one on Silver, they went up to the restaurant floor. As soon as they entered the large high-ceilinged restaurant Jack saw the war hero. “You mean he’s the one who’s supposed to inspire these girls to save their money for war bonds? He’s never saved a penny in his life! I’ve kept him in spending money ever since we joined the army on the same day.”

“Who is he?” said Silver. “My mother’s a bit on the vague side. She couldn’t remember his name.”

But before Jack could tell her, the war hero had broken away from the group around him and come plunging towards them. “You old bastard, Savanna! What are you doing here?”

“After you speak, I get up and say a piece,” said Jack. “They want the girls to get both sides of the question. You, you bludger!” he said elegantly, and shook his head disgustedly. He turned to Silver. ‘This is Sergeant Morley, V.C. Miss Bendixter.”

He was glad to see that Silver remained cool and didn’t gush. “My, we are honoured tonight. A real live V.C. winner.”

“I’ll say this for him,” said Jack. “Most of them don’t stay alive.”

Jack later has a confrontation with a lieutenant who tries to stop him entering, until Jack threatens to ‘drop him down the lift well. Pips or no pips’ and the lieutenant retreats:

“You would have hit him, wouldn’t you?” Silver said. “Or thrown him down the lift well.”

“Certainly. Don’t you think he asked for it?”

“I suppose so. But here! Do you always choose such crowded places for you assassinations? And when you’re with your lady friends? I feel a little like some floosie from Paddington.”

He stopped and looked down at her. “For that last remark, I should drop you down the lift well. I don’t know why, but one thing I hadn’t expected from you was snobbishness.”

She said nothing for a moment, and he thought she was going to walk away from him. Then she put her hand in his and suddenly he was aware of a new intimacy between them. It was as if they were old lovers who had patched up a quarrel, and there was none of the awkwardness that would have been natural in view of their short acquaintance. “I’m sorry, Jack. That was something I should never have allowed myself even to think. My apologies to the girls in Paddington.”

Jon Cleary, Australian, 1917-2010